| Complete Text and Photos of Ten Important Barack Obama Speeches from 2002-2008. | ||||

| October

2, 2002 Barack Obama speaks against a war with Iraq in Chicago, Illinois. |

July

27, 2004 Barack Obama delivers the Keynote Address at DNC in Boston, MA. |

January

8, 2008 Obama's passionate "Yes We Can" speech at school in Nashua, NH. |

January

20, 2008 Barack Obama speaks at Martin Luther King's church in Atlanta, GA. |

March

18, 2008 Barack Obama's inspiring US racial issues speech in Philadelphia, PA. |

| June

30, 2008 Obama's patriotic "The America We Love" speech in Independence, MO. |

July

24, 2008 Obama delivers his only European tour speech in Berlin, Germany. |

August

28, 2008 Obama's acceptance speech at the DNC in Denver, Colorado. |

October

27, 2008 Obama's speech in last week of campaign delivered in Canton, OH. |

November

4, 2008 Obama delivers his first speech as President-elect in Chicago's Grant Park. |

| Important

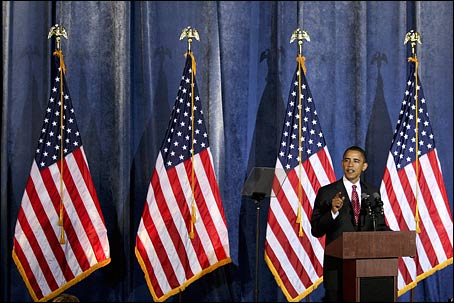

Speeches and Remarks of Barack Obama June 30, 2008 - Independence, Missouri |

| Obama delivers a patriotic speech - The America We Love - in Independence, MO. |

|

|

| Barack

Obama delivers a passionate speech on patriotism on June 30, 2008. The theme of the Independence, Missouri speech is "The America We Love." |

| Watch the Obama YouTube of Obama 's Campaign Speech in Independence, MO on June 30, 2008 |

|

June 30, 2008 Independence, Missouri Remarks of Senator Barack Obama: The America We Love On a spring morning in April of 1775, a simple band of colonists farmers and merchants, blacksmiths and printers, men and boys left their homes and families in Lexington and Concord to take up arms against the tyranny of an Empire. The odds against them were long and the risks enormous for even if they survived the battle, any ultimate failure would bring charges of treason, and death by hanging. And yet they took that chance. They did so not on behalf of a particular tribe or lineage, but on behalf of a larger idea. The idea of liberty. The idea of God-given, inalienable rights. And with the first shot of that fateful day a shot heard round the world the American Revolution, and America's experiment with democracy, began. Those men of Lexington and Concord were among our first patriots. And at the beginning of a week when we celebrate the birth of our nation, I think it is fitting to pause for a moment and reflect on the meaning of patriotism theirs, and ours. We do so in part because we are in the midst of war more than one and a half million of our finest young men and women have now fought in Iraq and Afghanistan; over 60,000 have been wounded, and over 4,600 have been laid to rest. The costs of war have been great, and the debate surrounding our mission in Iraq has been fierce. It is natural, in light of such sacrifice by so many, to think more deeply about the commitments that bind us to our nation, and to each other. We reflect on these questions as well because we are in the midst of a presidential election, perhaps the most consequential in generations; a contest that will determine the course of this nation for years, perhaps decades, to come. Not only is it a debate about big issues health care, jobs, energy, education, and retirement security but it is also a debate about values. How do we keep ourselves safe and secure while preserving our liberties? How do we restore trust in a government that seems increasingly removed from its people and dominated by special interests? How do we ensure that in an increasingly global economy, the winners maintain allegiance to the less fortunate? And how do we resolve our differences at a time of increasing diversity? Finally, it is worth considering the meaning of patriotism because the question of who is or is not a patriot all too often poisons our political debates, in ways that divide us rather than bringing us together. I have come to know this from my own experience on the campaign trail. Throughout my life, I have always taken my deep and abiding love for this country as a given. It was how I was raised; it is what propelled me into public service; it is why I am running for President. And yet, at certain times over the last sixteen months, I have found, for the first time, my patriotism challenged at times as a result of my own carelessness, more often as a result of the desire by some to score political points and raise fears about who I am and what I stand for. So let me say at this at outset of my remarks. I will never question the patriotism of others in this campaign. And I will not stand idly by when I hear others question mine. My concerns here aren't simply personal, however. After all, throughout our history, men and women of far greater stature and significance than me have had their patriotism questioned in the midst of momentous debates. Thomas Jefferson was accused by the Federalists of selling out to the French. The anti-Federalists were just as convinced that John Adams was in cahoots with the British and intent on restoring monarchal rule. Likewise, even our wisest Presidents have sought to justify questionable policies on the basis of patriotism. Adams' Alien and Sedition Act, Lincoln's suspension of habeas corpus, Roosevelt's internment of Japanese Americans all were defended as expressions of patriotism, and those who disagreed with their policies were sometimes labeled as unpatriotic. In other words, the use of patriotism as a political sword or a political shield is as old as the Republic. Still, what is striking about today's patriotism debate is the degree to which it remains rooted in the culture wars of the 1960s in arguments that go back forty years or more. In the early years of the civil rights movement and opposition to the Vietnam War, defenders of the status quo often accused anybody who questioned the wisdom of government policies of being unpatriotic. Meanwhile, some of those in the so-called counter-culture of the Sixties reacted not merely by criticizing particular government policies, but by attacking the symbols, and in extreme cases, the very idea, of America itself by burning flags; by blaming America for all that was wrong with the world; and perhaps most tragically, by failing to honor those veterans coming home from Vietnam, something that remains a national shame to this day. Most Americans never bought into these simplistic world-views these caricatures of left and right. Most Americans understood that dissent does not make one unpatriotic, and that there is nothing smart or sophisticated about a cynical disregard for America's traditions and institutions. And yet the anger and turmoil of that period never entirely drained away. All too often our politics still seems trapped in these old, threadbare arguments a fact most evident during our recent debates about the war in Iraq, when those who opposed administration policy were tagged by some as unpatriotic, and a general providing his best counsel on how to move forward in Iraq was accused of betrayal. Given the enormous challenges that lie before us, we can no longer afford these sorts of divisions. None of us expect that arguments about patriotism will, or should, vanish entirely; after all, when we argue about patriotism, we are arguing about who we are as a country, and more importantly, who we should be. But surely we can agree that no party or political philosophy has a monopoly on patriotism. And surely we can arrive at a definition of patriotism that, however rough and imperfect, captures the best of America's common spirit. What would such a definition look like? For me, as for most Americans, patriotism starts as a gut instinct, a loyalty and love for country rooted in my earliest memories. I'm not just talking about the recitations of the Pledge of Allegiance or the Thanksgiving pageants at school or the fireworks on the Fourth of July, as wonderful as those things may be. Rather, I'm referring to the way the American ideal wove its way throughout the lessons my family taught me as a child. One of my earliest memories is of sitting on my grandfather's shoulders and watching the astronauts come to shore in Hawaii. I remember the cheers and small flags that people waved, and my grandfather explaining how we Americans could do anything we set our minds to do. That's my idea of America. I remember listening to my grandmother telling stories about her work on a bomber assembly-line during World War II. I remember my grandfather handing me his dog-tags from his time in Patton's Army, and understanding that his defense of this country marked one of his greatest sources of pride. That's my idea of America. I remember, when living for four years in Indonesia as a child, listening to my mother reading me the first lines of the Declaration of Independence "We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal. That they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness." I remember her explaining how this declaration applied to every American, black and white and brown alike; how those words, and words of the United States Constitution, protected us from the injustices that we witnessed other people suffering during those years abroad. That's my idea of America. As I got older, that gut instinct that America is the greatest country on earth would survive my growing awareness of our nation's imperfections: it's ongoing racial strife; the perversion of our political system laid bare during the Watergate hearings; the wrenching poverty of the Mississippi Delta and the hills of Appalachia. Not only because, in my mind, the joys of American life and culture, its vitality, its variety and its freedom, always outweighed its imperfections, but because I learned that what makes America great has never been its perfection but the belief that it can be made better. I came to understand that our revolution was waged for the sake of that belief that we could be governed by laws, not men; that we could be equal in the eyes of those laws; that we could be free to say what we want and assemble with whomever we want and worship as we please; that we could have the right to pursue our individual dreams but the obligation to help our fellow citizens pursue theirs. For a young man of mixed race, without firm anchor in any particular community, without even a father's steadying hand, it is this essential American idea that we are not constrained by the accident of birth but can make of our lives what we will that has defined my life, just as it has defined the life of so many other Americans. That is why, for me, patriotism is always more than just loyalty to a place on a map or a certain kind of people. Instead, it is also loyalty to America's ideals ideals for which anyone can sacrifice, or defend, or give their last full measure of devotion. I believe it is this loyalty that allows a country teeming with different races and ethnicities, religions and customs, to come together as one. It is the application of these ideals that separate us from Zimbabwe, where the opposition party and their supporters have been silently hunted, tortured or killed; or Burma, where tens of thousands continue to struggle for basic food and shelter in the wake of a monstrous storm because a military junta fears opening up the country to outsiders; or Iraq, where despite the heroic efforts of our military, and the courage of many ordinary Iraqis, even limited cooperation between various factions remains far too elusive. I believe those who attack America's flaws without acknowledging the singular greatness of our ideals, and their proven capacity to inspire a better world, do not truly understand America. Of course, precisely because America isn't perfect, precisely because our ideals constantly demand more from us, patriotism can never be defined as loyalty to any particular leader or government or policy. As Mark Twain, that greatest of American satirists and proud son of Missouri, once wrote, "Patriotism is supporting your country all the time, and your government when it deserves it." We may hope that our leaders and our government stand up for our ideals, and there are many times in our history when that's occurred. But when our laws, our leaders or our government are out of alignment with our ideals, then the dissent of ordinary Americans may prove to be one of the truest expression of patriotism. The young preacher from Georgia, Martin Luther King, Jr., who led a movement to help America confront our tragic history of racial injustice and live up to the meaning of our creed he was a patriot. The young soldier who first spoke about the prisoner abuse at Abu Ghraib he is a patriot. Recognizing a wrong being committed in this country's name; insisting that we deliver on the promise of our Constitution these are the acts of patriots, men and women who are defending that which is best in America. And we should never forget that especially when we disagree with them; especially when they make us uncomfortable with their words. Beyond a loyalty to America's ideals, beyond a willingness to dissent on behalf of those ideals, I also believe that patriotism must, if it is to mean anything, involve the willingness to sacrifice to give up something we value on behalf of a larger cause. For those who have fought under the flag of this nation for the young veterans I meet when I visit Walter Reed; for those like John McCain who have endured physical torment in service to our country no further proof of such sacrifice is necessary. And let me also add that no one should ever devalue that service, especially for the sake of a political campaign, and that goes for supporters on both sides. We must always express our profound gratitude for the service of our men and women in uniform. Period. Indeed, one of the good things to emerge from the current conflict in Iraq has been the widespread recognition that whether you support this war or oppose it, the sacrifice of our troops is always worthy of honor. For the rest of us for those of us not in uniform or without loved ones in the military the call to sacrifice for the country's greater good remains an imperative of citizenship. Sadly, in recent years, in the midst of war on two fronts, this call to service never came. After 9/11, we were asked to shop. The wealthiest among us saw their tax obligations decline, even as the costs of war continued to mount. Rather than work together to reduce our dependence on foreign oil, and thereby lessen our vulnerability to a volatile region, our energy policy remained unchanged, and our oil dependence only grew. In spite of this absence of leadership from Washington, I have seen a new generation of Americans begin to take up the call. I meet them everywhere I go, young people involved in the project of American renewal; not only those who have signed up to fight for our country in distant lands, but those who are fighting for a better America here at home, by teaching in underserved schools, or caring for the sick in understaffed hospitals, or promoting more sustainable energy policies in their local communities. I believe one of the tasks of the next Administration is to ensure that this movement towards service grows and sustains itself in the years to come. We should expand AmeriCorps and grow the Peace Corps. We should encourage national service by making it part of the requirement for a new college assistance program, even as we strengthen the benefits for those whose sense of duty has already led them to serve in our military. We must remember, though, that true patriotism cannot be forced or legislated with a mere set of government programs. Instead, it must reside in the hearts of our people, and cultivated in the heart of our culture, and nurtured in the hearts of our children. As we begin our fourth century as a nation, it is easy to take the extraordinary nature of America for granted. But it is our responsibility as Americans and as parents to instill that history in our children, both at home and at school. The loss of quality civic education from so many of our classrooms has left too many young Americans without the most basic knowledge of who our forefathers are, or what they did, or the significance of the founding documents that bear their names. Too many children are ignorant of the sheer effort, the risks and sacrifices made by previous generations, to ensure that this country survived war and depression; through the great struggles for civil, and social, and worker's rights. It is up to us, then, to teach them. It is up to us to teach them that even though we have faced great challenges and made our share of mistakes, we have always been able to come together and make this nation stronger, and more prosperous, and more united, and more just. It is up to us to teach them that America has been a force for good in the world, and that other nations and other people have looked to us as the last, best hope of Earth. It is up to us to teach them that it is good to give back to one's community; that it is honorable to serve in the military; that it is vital to participate in our democracy and make our voices heard. And it is up to us to teach our children a lesson that those of us in politics too often forget: that patriotism involves not only defending this country against external threat, but also working constantly to make America a better place for future generations. When we pile up mountains of debt for the next generation to absorb, or put off changes to our energy policies, knowing full well the potential consequences of inaction, we are placing our short-term interests ahead of the nation's long-term well-being. When we fail to educate effectively millions of our children so that they might compete in a global economy, or we fail to invest in the basic scientific research that has driven innovation in this country, we risk leaving behind an America that has fallen in the ranks of the world. Just as patriotism involves each of us making a commitment to this nation that extends beyond our own immediate self-interest, so must that commitment extends beyond our own time here on earth. Our greatest leaders have always understood this. They've defined patriotism with an eye toward posterity. George Washington is rightly revered for his leadership of the Continental Army, but one of his greatest acts of patriotism was his insistence on stepping down after two terms, thereby setting a pattern for those that would follow, reminding future presidents that this is a government of and by and for the people. Abraham Lincoln did not simply win a war or hold the Union together. In his unwillingness to demonize those against whom he fought; in his refusal to succumb to either the hatred or self-righteousness that war can unleash; in his ultimate insistence that in the aftermath of war the nation would no longer remain half slave and half free; and his trust in the better angels of our nature he displayed the wisdom and courage that sets a standard for patriotism. And it was the most famous son of Independence, Harry S Truman, who sat in the White House during his final days in office and said in his Farewell Address: "When Franklin Roosevelt died, I felt there must be a million men better qualified than I, to take up the Presidential task But through all of it, through all the years I have worked here in this room, I have been well aware than I did not really work alone that you were working with me. No President could ever hope to lead our country, or to sustain the burdens of this office, save the people helped with their support." In the end, it may be this quality that best describes patriotism in my mind not just a love of America in the abstract, but a very particular love for, and faith in, the American people. That is why our heart swells with pride at the sight of our flag; why we shed a tear as the lonely notes of Taps sound. For we know that the greatness of this country its victories in war, its enormous wealth, its scientific and cultural achievements all result from the energy and imagination of the American people; their toil, drive, struggle, restlessness, humor and quiet heroism. That is the liberty we defend the liberty of each of us to pursue our own dreams. That is the equality we seek not an equality of results, but the chance of every single one of us to make it if we try. That is the community we strive to build one in which we trust in this sometimes messy democracy of ours, one in which we continue to insist that there is nothing we cannot do when we put our mind to it, one in which we see ourselves as part of a larger story, our own fates wrapped up in the fates of those who share allegiance to America's happy and singular creed. Thank you, God Bless you, and may God Bless the United States of America. |

| Complete Text and Photos of Ten Important Barack Obama Speeches from 2002-2008. | ||||

| October

2, 2002 Barack Obama speaks against a war with Iraq in Chicago, Illinois. |

July

27, 2004 Barack Obama delivers the Keynote Address at DNC in Boston, MA. |

January

8, 2008 Obama's passionate "Yes We Can" speech at school in Nashua, NH. |

January

20, 2008 Barack Obama speaks at Martin Luther King's church in Atlanta, GA. |

March

18, 2008 Barack Obama's inspiring US racial issues speech in Philadelphia, PA. |

| June

30, 2008 Obama's patriotic "The America We Love" speech in Independence, MO. |

July

24, 2008 Obama delivers his only European tour speech in Berlin, Germany. |

August

28, 2008 Obama's acceptance speech at the DNC in Denver, Colorado. |

October

27, 2008 Obama's speech in last week of campaign delivered in Canton, OH. |

November

4, 2008 Obama delivers his first speech as President-elect in Chicago's Grant Park. |

| Daily Photo Journal Timeline of President-elect Barack Obama. | |||

| November

4, 2008 Obama's Victory Day |

November

2008 77 Days - Section One |

December

2008 77 Days - Section Two |

January

2009 77 Days - Section Three |

| Historic

change gives hope as Obama becomes President-elect. |

Obama's

transition team selects key cabinet posts. |

Obama

completes cabinet and takes family vacation in Hawaii. |

Obama

prepares for historic Inauguration as 44th President. |